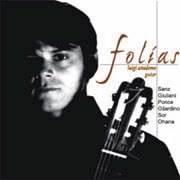

Folías

Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829)

Variazioni sul tema della Follia di Spagna op.45

Manuel M. Ponce (1882-1948)

Variations sur "Folia de España" et Fugue

Angelo Gilardino (1941)

Variazioni sulla Follía (Studi da Francisco Goya)

Fernando Sor (1778-1839)

Les Folies d'Espagne Variées et un Minuet op.15a

Maurice Ohana (1914-1995)

Tiento

La parola Follia ha oggi un significato inequivocabile, seppur sotto questo significato si celino diversi sensi. Tra i due poli estremi - la Follía come malattia e la Follía come entusiasmo - ogni artista cerca la sua dimensione, il suo luogo segreto. Con ciò il tema della Follía di origine iberica - una danza dal movimento veloce - forse ha poco o nulla a che vedere.

Il significato di questo percorso, che parte da Sanz per approdare all'enigmatico Ohana e passa per pezzi diversi per stile e poetica, ha il suo centro nelle Variazioni sulla Follía di Angelo Gilardino, non a caso pensate dall'autore come studi da Francisco Goya. A quella poetica ci riferiamo quando cerchiamo nel suono della chitarra il senso delle nostre percezioni e il modo di restituirle a chi ci ascolta.

L'opera di Gilardino segna la Follía attraverso la cifra dell'allucinazione: solo attraverso di essa è possibile svelare il mondo per quello che è. Non rinunciando alla tradizionale scrittura densa di contrappunti, di canti interrotti e reiterati, di dinamiche contrastanti, Gilardino rielabora la Follía immergendola, come un antico alchimista, in diversi e sconosciuti elementi sonori, facendola essere di volta in volta altro da sé, alienata e alienante. Impossibile da concludere, il processo di trasformazione sfocia nella citazione del tema di Sor, come richiamo a un altro nobile della chitarra che, come lui, ha scelto il suono per conservare pensieri profondi e tormentati.

Giuliani e Sor, rispetto a questa linea, sembrano essere estranei. Eppure la loro compattezza è venata da segni di malinconia che affiancano, ad esempio, la rievocazione esuberante del ritmo di fandango che sottolinea la provenienza iberica del tema.

Lontana appare la musica di Gaspar Sanz, quasi inudibile per noi uomini del XX secolo. Devastante, invece, il Tiento di Maurice Ohana - compositore non chitarrista che con le sue mutazioni attraversa, lacerandolo, il tema della Follía.

Una composizione di tutto rilievo è quella di Manuel Ponce, altro compositore non chitarrista legato alla figura di Andrés Segovia. Ponce, ancora immerso in un linguaggio tradizionale che fa dell'armonia il nucleo dell'espressione, tenta di scrivere un'opera monumentale (che si chiude non a caso con una fuga) ispirato dalla letteratura pianistica, ri-componendo il tema in vari modi ed espandendone la forma. Il risultato è una sintesi del suo sapere musicale e di una poetica, quella appunto di matrice segoviana, che è un ineliminabile punto di vista nel modo di intendere la chitarra.

Fare una raccolta di questi cicli di variazioni ha avuto due scopi: attraversare in modo lineare la storia della chitarra; mostrare che l'espressione artistica da noi ricercata appare sotto diverse forme, tutte vere e false nello stesso tempo, in continua trasformazione e per questo stessa ragione estranee a noi, ma vere artefici di quella "divina mania" che sola può rendere l'aedo moderno tanto forte da reggere l'impatto con il non senso, causa e conseguenza della nostra Follía.

Nowadays the word insanity brings with it a meaning which doesn’t leave any room to doubt, even though there may be several meanings concealed in it. Between the two opposite poles of insanity conceived as a disease, and insanity conceived as enthusiasm, each artist is constantly looking for their particular characteristic, and secret hiding places. The Iberian theme -the Folias - (a fast moving dance) doesn’t have much to do with all this.

Such a path has its origin in Sanz, and ends up with the enigmatic Ohana, touching pieces which are divided by different styles and poetics, and it finally finds its center in Angelo Gilardino’s Variazioni sulla Follia. It is not only by chance that they have been conceived by their author as studies of Francisco Goya. Every time a guitarist is looking into the guitar sound to be able to find the meaning of human perceptions, and a way to give them back to their audience, there is a reference to that particular poetic path.

Angelo Gilardino’s work rides Follía through hallucination. It is only through hallucination that the world can be revealed in its true sense. Without giving up the traditional way of composing with its counterpoint, its interrupted and repeated themes, and its opposite dynamics, Gilardino works out Follía again, and dives into it, as an ancient alchemist, to develop diverse and unknown sounds. This process transforms Follía into something that does not belong to the author, into something that can be, at the same time, both alienated and alienator. It is impossible to accomplish completely such a kind of alchemistic process, and this is the reason why it ends up with the quotation of Sor, another great guitarist who has chosen to render and preserve the deepness and the torture of his thoughts by means of a specific sound.

As far as this direction is concerned, Giuliani and Sor might seem completely alien, yet their solidity is tinged with sadness which marches side by side, for instance, with the fandango lively and rhythmic reminiscence, which underlines the Iberian origin of the main theme.

Gaspar Sanz compositions sound distant and almost impossible to listen to, to our twentieth century ears. On the other side, the Tiento of Maurice Ohana breaks through the Follía theme, and completely tears it apart, enriching it with the mutation of a non-guitarist composer.

Ponce is another non-guitarist composer connected to Andrés Segovia’s figure, whose compositions are of great relevance. He is surrounded by a traditional musical language, and this makes harmony the real core of his expression. He makes the effort to compose a monumental work, that is inspired by piano compositions, and that ends — not by chance — with a fugue. He re-composes the theme again and again in several different ways, broadening its shape. The result of this process is a synthesis of his musical know how melded with some kind of poetry of Segovian origin, which can be considered a milestone in the way guitar sound has been conceived.

Preparing a collection containing these cycles of change can carry two main purposes: walking through guitar history in a linear way, showing at the same time that the artistic expression we are looking for can appear in different ways, each one of them under constant mutation, and both true and false at the same time. This can appear alien to our perception, nevertheless it is part of that divine madness which is the only component that can make the modern bard strong enough to bear the impact with lack of meaning, which can be considered the cause and the consequence of our insanity. (transl. MAYA BODO)